My dear Scribes,

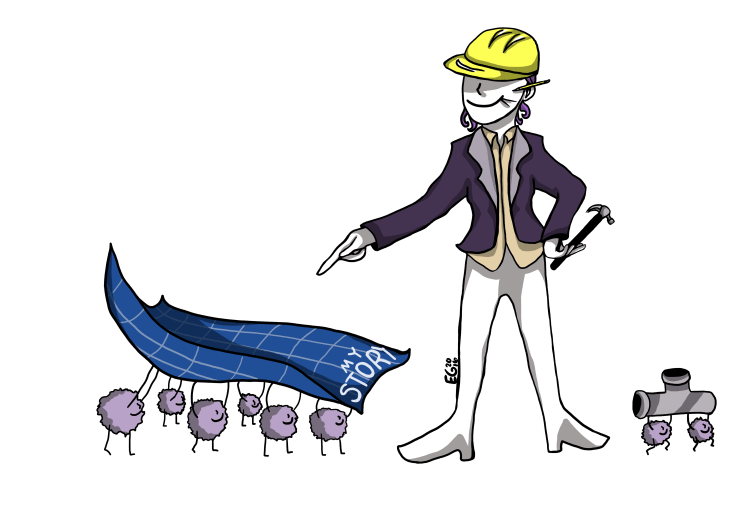

Today marks the fourth birthday of my blog. I don’t typically ascribe to the sentimentality of anniversaries — it’s only one day, after all (and everyone knows that time is a social construct!). But when I saw the notification this morning, I was temporarily lifted from the fog of my undergraduate life. I ascended from my literary analyses and anthropological articles and was reminded of myself at sixteen years old. I was a sophomore in high school who had accumulated too many poems, and I needed a place to put them. Since then, Stellular Scribe has been a constant writing refuge for me from my over-scheduled life. One day, I hope to settle here more permanently, to share my first, most precious passion more consistently.

To commemorate four years on the internet, I want to share with you a recent piece I wrote for a fiction workshop, entitled “A Tide Come May.”

Thank you, all, for your support. For your attentive reading. For your inspiration.

Finding the way out to sea too cryogenic in salt, she sunk into the sand at the shore. Here was an exit too vague and cold to cross, where eels of foam avoided her toes and sizzled under the sun. Here was the spoke in the sand and the angled footprints of the fisherman and the silvery dust of mishandled scales. A man too tanned, too thick haired and black eyed, to be mistaken for her father stood knee-deep in the surf and repealed his line from the sea.

The Rooster’s shadow overcast her.

“…already knew about historicist nihilism, but Hegel still changed my life. I feel, huh, like I’ve evolved as a thinker, you know?”

Her inner ear prickled at his voice. Here was the Hawaiian-shirt clad tourist, who, while strolling the beach with idealism under his arm, had spied her reading in the dunes and taken it upon himself to question her taste in literature. He wore a squat hat — a hat that she thought new mothers might stuff over toddler ears. He had told her his name, but all she could remember of the exchange was the way he scratched his sunburnt neck, like a preening rooster. He went on roosting in her sun, following her from the beachgrass to the minefield of broken shells at the bank to where she sat now, blockaded at the water’s edge.

Fly away, she wanted to say. Go find a nice hen to squawk at.

The too-tanned man, who would never have been picked out as her blood against a beach of pale, sunbathing flesh, took pride in his cast. She saw it in the way his eyes longed after the lure whipping into invisibility across the waves. The satisfying latch of the lead sinker, the taut reflection of the line as the reel snapped against his hands — his mechanics exhaled an intertidal joy. She envied that clarity, that sense of belonging in the space between low and high tide.

The Rooster cawed for attention.

“You should read Phenomenology of Spirit, if you want something more substantial. I’ll say, though, it’s not exactly a light beach read, ha! You know, when I saw you I thought that not a lot of girls…”

Finally, the water stretched its invisible hands to her feet. She thanked it with her fingers, with her palms filled with wet sand. The Rooster’s own knobby toes slipped under the tide.

“Jesus, that’s cold!” He hopped out of the water’s way.

She blinked at him. “To be honest, Roo—”

“Roger.”

“I’ll be honest.” She cleared her throat. “You have good intentions, I’m sure. Great. The best. So you might not realize —”

That you’re emitting potent stalker vibes and I’ve never in my life cared about Hegel and also I don’t know you.

She didn’t say anything else, because the too-tanned man’s arm locked. His rod bowed. Old ladies wearing floppy sun hats stopped on their waterside stroll to gasp at something in between the waves.

“Realize?” The Rooster cocked his head, and his toddler hat almost slid off the side of his head.

A saline breeze brought her to her feet. “Shark.”

“What?”

She tossed her book up into the dry sand and pointed towards the crowd gathering around the too-tanned man. “Shark!”

***

The too-tanned man, who was her father, would compose poetry to the shark if he knew the right words. But he was the crease in the white collar of America and had been sewn into the silence of masculine pride. He could only express his devotion in the act of drawing, by pooling his strength into removing the shark from his power. Though she did not look like him — she was too sallow in complexion and prone to angularities — she always sensed that she thought like him. Where he did not speak for the shark, he manifested. It was in his intensity on the thrill of the catch, the meditation of extraction, the worship of an ancient aquatic foe. They shared in their longing on the cusp of two worlds.

The Rooster followed her, predictably, to the scene. She left his clucking behind her, uninterested in his inevitable attempts to philosophize a shark.

She splashed out to her father and saw, quite clearly, that Hollywood-hailed triangle of gray. As the clear belly of the wave stretched vertically, a dorsal fin sliced into view. A crowd of Vineyard Vines spokesladies and geriatric men fiddling with their croakies gathered on the side of the earthbound. A man in patriotic swim trunks hollered, “Thas a big boy!”

She imagined it as an invaded moment of privacy, as if all of Middle America had peered through the hospital door to watch the sea, splayed on its back, give thrashing, tearful birth. She wanted to shoo them back into the white enamel corridor, back to their terrestrial existences, and tell them, “Family only, please.”

The Rooster’s voice rose from the sand. “Hey, you should stay back! Sharks have layers of teeth, fifty teeth, sharp as knives. I can remember a time —”

“How is she?” Her voice was a whisper at her father’s side.

“Four feet, brown shark, only a juvenile.” With one hand he shifted his cigar to the corner of his mouth and clamped it between his teeth. With the other hand, he reeled. And reeled. And reeled.

The line sung a high-pitched note in the wind. There was no need to say anything else; she knew what lyrics were being transposed in their thoughts. There was a solemnity that accompanied reeling in a shark. The goal of fishing, as they understood, was to sustain a dinner table, to tie the biblical knot between family and the kingdom of oceanic offerings. The shark did not fulfill that goal; but still they must drag it in, despite its violent desperation, so that they could discharge it.

She was reminded of five years ago when she stood knee-deep in the sea on this same bank with her own skinny pole. Fishing was all there was to do on a May afternoon when the water was too cold to swim in — and she had been praying, just loud enough that she could hear her own words mingle in the grumble of the waves. She prayed to the current that spiraled the bloodworm at the end of her hook, to the curiosity of schools of kingfish, to the enthusiasm of crabs reaching through the murky soup of seaweed for her bait.

It was a self-contained ritual that her father carried out now, mumbling under his breath. Only here was the shark, the antithesis to Christ’s Galilean tilapia, flipping its powerful tail over the break of white water. Here was the sea, weeping to lose her eldest daughter. She joined in her father’s prayer, that they may come quietly. Peacefully.

Of course, the crowd soaked up the drama of the display.

“I didn’t know there were sharks here!” a woman exclaimed.

“That’s it, I’m never going in the water again.”

God forbid there are sharks in the Atlantic.

A stream of sweat slipped parallel to the vein straining in her father’s neck. She knew how it felt — like pulling a sack of bricks by a thread. Soon his arm would go numb; his thumb would blister.

“Now!” he said.

***

She grabbed the line as it slackened and pulled it backwards towards the sand. Like elastic, the waves retracted, offering up the shark. Its skin glistened as the sun, foreign and forceful, seeped into it. Jaw agape, finely pointed teeth lined in its own blood, eyes yellow with liquid terror, gills begging against the air. It swung out its tail like a whip and the crowd took a collective breath.

Her father held out his arm as he sloshed towards the bank. “Stay back. She’s scared.”

“Is that a real shark?” someone asked.

Her father didn’t answer. He knelt beside the creature and pulled a set of pliers out of his pocket.

She staked her knees in the wet sand and placed her palm on the back of the shark’s skull. It felt like suede beholding flexible cartilage as the nerves in its vertebrae fired, retired, and fired again. With her other hand she pinned the tail, and felt its livid life force punch against her bony matter. The shark’s musculature seized and released as it volleyed between twisting out of her grip and resigning to her weight.

The process of removing the hook involved a coordination between her and her father. An exchange, if it were, of poetics. His plier hovered in the space between the shark’s upper and lower rows of teeth as she wrangled the body and splashed water onto its back. The white inner flesh suctioned, the unseen steel bent into submission, a bubble of blood popped in the back of its throat.

The hook emerged as a crumpled thing, and the shark reared its head.

She stroked a line down its dorsal fin, and she marvelled at her distinctness. “Can I…can I take her back?”

Her father wiped his bloody hands off in the sand and nodded. “Be careful with her tail.”

Before the sea could lap around her ankles, she wrapped her arms around the belly of the shark. One hand encircled the base of the caudal fin. She slid its pectoral into the crook of her elbow. Its belly heaved, strangely prickly and cool, against her own, and she had to enclose the heavy-set body within the physical space between her forearms and ribs.

She glanced back at the crowd, suddenly self-conscious of her appearance as an awkward redeemer — but rather than the Messiah cradling his lamb, she teetered to clutch sixty pounds of jagged shark, of anxious, sharp-jawed brawn.

The Rooster was gone. And she found it fitting, somehow, that as she had maneuvered his abstractions she now held tight to a most certain reality, an extraction of that vague, cold sea. A sea too cryogenic for her to know. But this shark, this poetic actor that her father had accepted at the end of his line, could transcend the suspended animation of the water’s surface. Could out-swim the dialectical crud of sea-sand-surf, thesis-antithesis-synthesis.

She turned her back to the lingering spectators and walked out to sea. As shells crunched beneath her feet, she knew that she had to go deeper, further, until she became numb to the cold. Until the intertidal zone was crossed, and the shark could feel again.

© 2018 Stellular Scribe